By Jonathan Muir

When I booted up InFAMOUS 2 I decided I was going to be an utter bastard. Placed in the shoes of the near-invincible lightening-powered demigod Cole McGrath, with the choice of saving the innocents of New Marais or senselessly murdering them, I chose the latter. The game is called INFAMOUS, right?

InFAMOUS 2 is a great game, but it illustrates some of the problems with moral choice systems in videogames. Morality is a murky, complex concept in real life, but in games it’s usually presented as a hilariously simplistic choice between Good or Evil (with a capital G and E, respectively).

Some games have tried to work around this – Mass Effect’s Renegade versus Paragon mechanics, or the karma system of the Fallout series – but in practical terms you’re always going to be presented with a choice between rescuing orphaned puppies from a fire or drop-kicking them into a river.

More often than not these moral choice systems will encourage you to pick one side of the moral coin and stick to it. The top tier abilities in InFAMOUS 2 are only granted to players who are really good or really bad – you don’t get any awesome Neutrality powers for being indifferent towards everyone.

The issue with this is that both moral paths must be balanced from a gameplay standpoint. You can’t reward players disproportionately for playing Good or playing Evil because then it’s no longer a choice. Players will inevitably go for the path of least resistance or the one that gives the most benefits.

In which case the player’s decision whether to be ‘good’ or ‘evil’ becomes arbitrary. In BioShock, for example, rescuing or killing the Little Sisters rewards you with pretty much the same amount of ADAM, so the choice really becomes whether you want to see the “good” or the “bad” ending.

For my money, the best use of a moral choice system is in BioWare’s Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic. For a start, it helps that the whole Star Wars mythology is built on the struggle between the ‘dark’ and ‘light’ sides of the Force, so a binary Good versus Evil moral choice mechanic doesn’t seem so out of place.

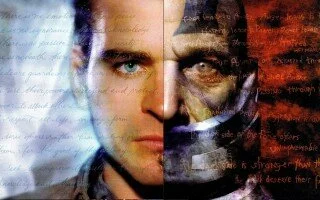

But what makes KOTOR’s moral choice system so effective is the way it’s weaved into the story. You start the game as your usual custom-built RPG protagonist, embarking on a quest to stop the warmongering Sith lord Darth Malik, who has usurped his master Darth Revan and threatens to conquer the universe. As you go about your intergalactic romp, your moral choices affect whether your character is more aligned with the Dark or Light side of the Force.

But – SPOILER ALERT – it transpires that you are Darth Revan, brainwashed by the Jedi so you wouldn’t be a threat to the galaxy. It sounds hammy on paper, but in the game it’s an effective plot twist, one that forces you to consider all kinds of uncomfortable questions about your moral choices.

If you’ve been playing as an unbridled tyrant up until that point, does that mean Revan is irrevocably an evil person? If you’ve been a faultless cherub of a player, does that mean Revan can do good? If Revan’s memories have been erased prior to the events of the game, are you even playing the same character?

Even though KOTOR’s moral choice system is often as simplistic as many of the others I’ve mentioned, it actually has something deep to say about morality. Is Good or Evil intrinsic and unchangeable? Or are they complex intangibles, dependent on context and experience? The success of KOTOR’s moral choice system is that it asks these kinds of difficult questions, and more games could learn from its example.

You can find more of Jonathons work here.